On November 26, ConocoPhillips – one of the largest oil and gas exploration and production companies in the world – announced that it plans to sell its 8.4% stake in the Kashagan deposit, located in offshore Kazakhstan, to India's ONGC for US$5 billion. ConocoPhillips may have realized that the real name of the Kashagan deposit is "Kash-is-gone deposit."

On November 26, ConocoPhillips – one of the largest oil and gas exploration and production companies in the world – announced that it plans to sell its 8.4% stake in the Kashagan deposit, located in offshore Kazakhstan, to India's ONGC for US$5 billion. ConocoPhillips may have realized that the real name of the Kashagan deposit is "Kash-is-gone deposit."

The Kashagan deposit is not just any deposit; it's one of the largest, if not the largest discovery of the past thirty years. With an estimated commercial reserve upwards of 12 billion barrels and a peak planned production of about 2 million barrels a day, Kashagan was thought to be an amazing addition to the portfolio of any company.

So why is Conoco trying to get out? Conoco's loss highlights some important truths in the oil exploration and development game:

Projects are becoming more technologically challenging.

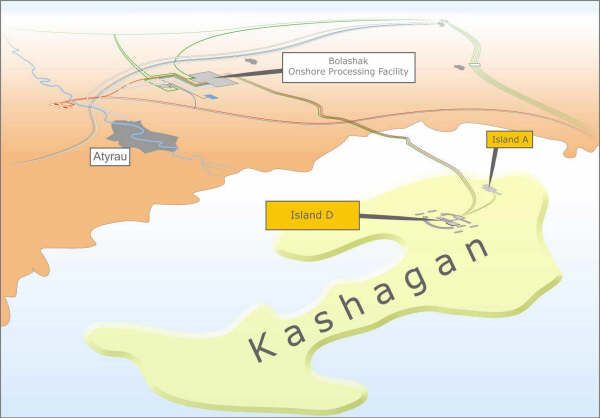

The location of Kashagan is far from ideal: The field sits offshore in the Caspian Sea and is subject to harsh weather, with temperatures that can range from -35 to +40° Celsius. The low temperatures in the winter combined with the shallow water and low salinity means that this part of the Caspian Sea is frozen for almost five months of the year. As you would expect, giant blocks of ice make construction and production of oil rather difficult.

Geologically, Kashagan also faces many technological hurdles. The reservoir is located 4,200 meters below the seabed and is highly pressurized. Though the crude oil is relatively light, the associated gas contains a very high level of sulfur. High levels of sulfur are bad for oil production – in certain forms, it's highly toxic and flammable, and if it's still present when the product is burned, it leads to acid rain. At Kashagan, the level of sulfur is so high that certain workers have to wear masks to avoid poisoning.

All of these problems have put Kashagan woefully behind schedule and over budget: the field was supposed to begin production in 2005 at a cost of US$57 billion. The field is now slated to flow its first barrel of oil in 2013 at a cost of US$187 billion. Not only is the Kash-is-gone deposit costing almost 250% more than expected and almost a decade behind schedule, it's a triple whammy: The initial production will be much less than previously thought.

Countries are trying to increase taxes and keep more for themselves.

As daunting as the technology problem is at Kashagan, it still pales in comparison to the complexity of the taxation system that the Kazakh government has put in place.

The rules of taxation at Kashagan are much more complicated than with most other production sharing contracts (PSCs). Even experienced fiscal analysts have been exasperated when trying to model just how much the government is taking away from the contractors through a myriad system of taxes, profit-sharing agreements, and other payments.

The Kazakh government has also not done itself any favors by regularly attempting to renegotiate the original contract to its own benefit. The most serious threat came in 2007, when the parliament passed a law that allowed the government to alter or cancel contracts at will with foreign oil companies. In a world where business is looking for stability, Kazakhstan is simply not giving any.

China, Russia, and India are the ones taking the big risks.

China's proposed US$15 billion takeover of Nexen Inc., Russia's US$55 billion takeover of TNK-BP, and now ONGC's US$5 billion takeover demonstrate one thing:

American companies are no longer at the forefront of the mergers and acquisition game.

China is willing to put down hundreds of billions of dollars into politically unstable Africa. Russia now not only has the biggest publicly traded oil company in the world (we covered that in a recent Dispatch), but is also beginning to explore the vast resources of the Arctic. India is beginning to get in the game, as the Kashagan acquisition was on the heels of another US$1 billion buy of Hess' 2.7% stake in the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli field, which is another oil project in the Caspian.

Overall, we are beginning to see American companies sell their stakes in foreign projects to Asian companies – a trend that will likely continue as Asia's desire for energy security prompts countries there to scour the globe for the best resources.

Putting It All Together

ConocoPhillips didn't get into Kashagan because it liked the challenge. It simply had little choice; at the time, this deposit was one of the best oil assets in the world, and oil companies are always under pressure to replenish their reserves.

The age of easily accessible oil is long gone; and even if companies can continue to make discoveries with the size of Kashagan (already highly unlikely), they're going to run into the same technological, environmental, and geological problems that Kashagan is facing right now.

To turn the screw yet a little more, countries with the best resources know they have something that all the firms want – and you can be sure that they'll try to extract as much as they can from the "big, bad foreign oil companies." This isn't a phenomenon exclusive to Kazakhstan. Countries in Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Asia alike are looking at ways to increase their government's share of the pie.

Even if they get past both of these problems, they'll have to compete with the new Asian energy superpowers that are sparing no expense when it comes to large oil projects.

Challenging geology, rising costs, greedy governments, and fierce competition for assets. It's easy to see that, short-term fluctuations aside, there's nowhere for oil to go but up.

By Marin Katusa

В Атырау -10

В Атырау -10