Replicas of an ancient monument in Palmyra that has apparently survived attempts by Islamic State to demolish it are to be erected in London and New York.

Replicas of an ancient monument in Palmyra that has apparently survived attempts by Islamic State to demolish it are to be erected in London and New York.

The 15-metre structure is one of the few remaining parts of the 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel in the Syrian city. Isis fighters all but razed the temple as they systematically destroyed Palmyra over the past year.

The construction of the replicas will be the centrepiece of events for world heritage week, planned for April with a theme of replication and reconstruction. It has also been characterised as a gesture of defiance against religious extremists' attempts to erase evidence of the Middle East's pre-Islamic history.

Founded in AD32, the temple was consecrated to the Mesopotamian god Bel and formed the centre of religious life in Palmyra. In keeping with many ancient temples, it was converted into a Christian church during the Byzantine era, and then into a mosque when Islam arrived in the area.

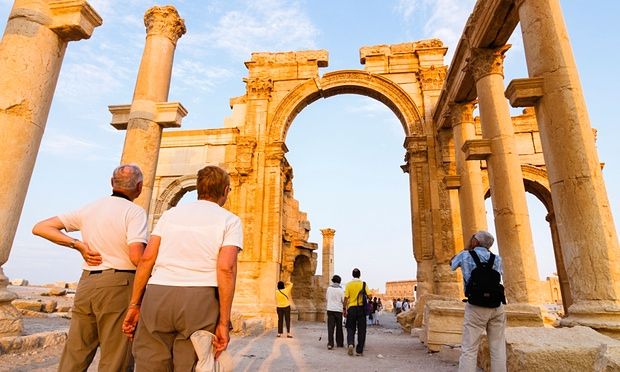

Known as the Pearl of the Desert, Palmyra – which means city of Palms – lies 130 miles (210km) north-east of Damascus. Before the Syrian conflict erupted in 2011, more than 150,000 tourists visited the city every year.

The Temple of Bel was considered among the best preserved ruins at Palmyra, until confirmation of the destruction in August. Isis also beheaded Khaled al-Asaad, the 82-year-old Syrian archaeologist who had looked after Palmyra's ruins for four decades, and hung his body in public.

Building a copy of the temple entrance has been proposed by the Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA), a joint venture between Harvard University, the University of Oxford and Dubai's Museum of the Future that promotes the use of digital imaging and 3D printing in archaeology and conservation.

In collaboration with Unesco, the institute began distributing 3D cameras to volunteer photographers earlier this year to capture images of threatened objects in conflict zones throughout the Middle East and north Africa.

The images are to be uploaded to a “million-image database" that it is hoped can be used for research, heritage appreciation, educational programmes and eventually 3D replication – including full-scale projects.

The destruction of the Temple of Bel came too soon for the site to be included on the IDA's database, but researchers have been able to create 3D approximations using thousands of two-dimensional photographs.

Alexy Karenowska, the IDA's director of technology, said the renderings would be used to recreate the arch through a combination of 3D printing computer-controlled machining techniques. The pieces will be made off-site then assembled in place in Trafalgar Square and Times Square.

Karenowska said the scheme would hopefully help to highlight the international importance of cultural heritage. The Temple of Bel influenced classical styles of architecture that spread throughout Europe during the Roman Empire, which once extended to the banks of the Euphrates, she said.

“We tend to think about cultural heritage in a somewhat parochial way," Karenowska said. “We also think of other people's cultural heritage as being something that's particular to them.

“We see that very much with the Middle East. People in the west find it very easy to say that the Middle East has this great cultural heritage and this problem [of its destruction] is something that's happening to them.

“The idea is to underline that cultural heritage is something that's shared between people. It's about people's roots and it's important to recognise also that this is something that as humans we do all understand on some deep level."

Roger Michel, the IDA's executive director, told the Times: “It is really a political statement, a call to action, to draw attention to what is happening inSyria and Iraq and now Libya. We are saying to them 'if you destroy something we can rebuild it again'. The symbolic value of these sites is enormous. We are restoring dignity to people."

Given that the temple has already been targeted in Syria, Karenowska accepted that building the arches could pose a security risk, although she downplayed its impact. “A building like the National Gallery or Trafalgar Square, these are major targets by virtue of what they are," she said.

“Simply by placing a thought-provoking piece of art in one of those spaces, the level of heightened risk is very limited. This is something we are thinking about very carefully and that people involved are thinking about on a day-to-day basis."

Source: the guardain.com

В Атырау -10

В Атырау -10