The plant researcher sporting two gold teeth points out the window of his Soviet-era SUV and shouts, “See! It’s like we told you!” Nursagim Ashikbayev, 76, springs out of the car and walks toward a gash torn by unknown diggers into an apple orchard along a steep hillside. “Climate change, fire, wind, insects, and livestock are all degrading the wild apple forests,” says Nurzhan Mukhamadiyev, Ashikbayev’s colleague at Kazakhstan’s Institute for the Conservation and Protection of Plants. “But one of the biggest problems is, people are building big summer houses here, then they buy dump trucks full of topsoil illegally taken from the surrounding mountains to fill in their gardens,” businessweek.com reports.

The plant researcher sporting two gold teeth points out the window of his Soviet-era SUV and shouts, “See! It’s like we told you!” Nursagim Ashikbayev, 76, springs out of the car and walks toward a gash torn by unknown diggers into an apple orchard along a steep hillside. “Climate change, fire, wind, insects, and livestock are all degrading the wild apple forests,” says Nurzhan Mukhamadiyev, Ashikbayev’s colleague at Kazakhstan’s Institute for the Conservation and Protection of Plants. “But one of the biggest problems is, people are building big summer houses here, then they buy dump trucks full of topsoil illegally taken from the surrounding mountains to fill in their gardens,” businessweek.com reports.

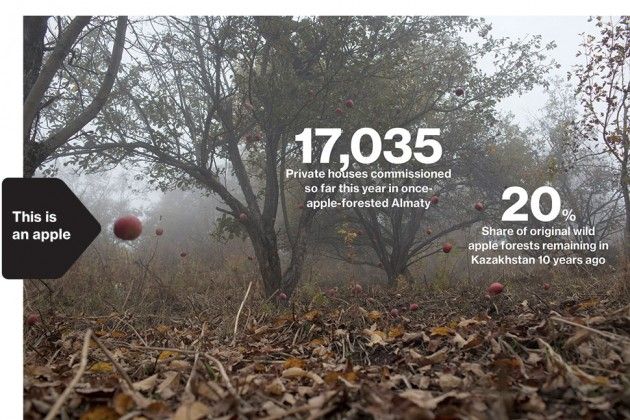

Apples were once the heart of Kazakhstan. Its former capital Almaty was once called Alma-Ata, or Father of Apples. “This is the place of origin of a lot of different crops, like apples, walnuts, and apricots. It is the genetic epicenter of these fruits and nuts,” says Evan Meyer, regional agricultural officer for the U.S. Agency for International Development. The situation around Almaty is bleak. “For 30 to 40 kilometers in every direction from the city up into the mountains, there is almost nothing left of the wild forests,” says Mukhamadiyev, an entomologist. “This is the motherland of wild apples. If the situation is not dealt with soon, there will be greater loss of territory.”

The shrinking of the wild apple forests in the former Soviet republic will have economic consequences for the apple industry elsewhere, according to researchers in the U.S. Some Kazakh strains show resistance to costly diseases, while others use water more efficiently or are drought-tolerant. “Varieties with these traits could potentially add billions in efficiency to the market,” says Gennaro Fazio, a U.S. Department of Agriculture plant geneticist. “If you lose it, it’s gone. It’s not going to be a source to draw upon—and we’re not only talking about the U.S. market, we’re talking worldwide.”

Biodiversity can fuel commerce. “A cider producer came to taste my weird-tasting Kazakh apples to make new flavors,” says Thomas Chao, a horticulturist and curator of the largest and most diverse collection of apple trees and other genetic material in the world, at the USDA’s orchards in Geneva, N.Y. He has cultivated trees grown from thousands of seeds collected in Kazakhstan from 1989 to 1996. “The wild apple material might have a big chance to become cider material in the future.” A shortage of cider apples in the U.S., which are more bitter than the so-called dessert apples found in supermarkets, has brewers looking overseas. Says Ben Watson, author of Cider, Hard and Sweet: “Now we are playing catch-up since cider has grown so popular.”

Cider makers will find little fruit around Almaty, a city now more famous for its smog than its apples. “Our research showed that only around 20 percent of the wild apple forests were left, and that was 10 years ago. We can say that there are almost no wild apple forests around Almaty,” says Gaukhar Mukhanova, director of the Aimak Dzhangaliev Laboratory at the Almaty Botanical Gardens. “We don’t export apples anymore. We only export oil.”

The housing market is taking its toll as well. In the first eight months of 2014, more than 17,000 houses were commissioned in the city, says Maxim Dyomin, senior consultancy manager for Veritas Brown, part of Cushman & Wakefield. The rich “are driven more by the desire to have their own standalone villa as an ultimate housing achievement—a family estate,” he says. “There have been cases of illegal construction in national parks and protected territory.”

Another threat to the apples comes from Almaty’s bid to host the 2022 Winter Olympics. Kazakhstan would see a win as a way to trumpet the rise of its economy, based primarily on oil. While some sporting and hotel infrastructure is in place, more is planned—and the fragile ecosystems around the city would suffer.

The country has made some efforts to preserve the wild apple forests. Established in 2010, the Zhongar-Alatau State National Nature Park, totaling 879,000 acres on the Chinese border, is home to the endangered Malus sieversii, a precursor to today’s hybridized apple. But the “father of apples” has less and less fruit to justify its name. “We need to save the forests for future generations, and we need to protect the genetic material as well,” says Mukhamadiyev, the entomologist. “Right now we’re growing summer homes and not apples.”

В Атырау 0

В Атырау 0