Illustration by Alexander Hunter/The Washington TimesAs the leaders of more than 50 nations hold the third Nuclear Security Summit in The Hague this week, there will be no shortage of issues to discuss or influential voices to be heard. While in global terms, ours is a young country, I believe none can bring greater relevant experience than Kazakhstan, washingtontimes.com reports.

Illustration by Alexander Hunter/The Washington TimesAs the leaders of more than 50 nations hold the third Nuclear Security Summit in The Hague this week, there will be no shortage of issues to discuss or influential voices to be heard. While in global terms, ours is a young country, I believe none can bring greater relevant experience than Kazakhstan, washingtontimes.com reports.

When my country gained independence in 1991, we found ourselves the inheritor of the world’s fourth-largest nuclear arsenal. We immediately decided to renounce these weapons and transferred them under great security to the Russian Federation.

There was good reason for Kazakhstan to set such a bold lead and for the decision to be so popular among our citizens. No country — nor people — has suffered more in peacetime from the terrible impact of nuclear weapons than our own.

For more than 40 years, the Semipalatinsk test site in northern Kazakhstan was the scene for nearly 500 Soviet nuclear explosions. These tests, in our atmosphere and under our land, saw more than 1 million unprotected people exposed to radioactive fallout and left vast tracts of land seriously contaminated. We continue to pay a heavy price in terms of human health and on our environment.

Our world may thankfully have moved away from the tensions and confrontation that led to Semipalatinsk being established. This does not, of course, mean the threat from nuclear weapons has disappeared.

What is particularly worrying is that recent decades have seen the threat from violent terrorist groups grow both in number and in their ferocity. By their sheer disregard for human life, they have raised fears of what they might do if they could get their hands on nuclear devices. It is why President Obama rightly warned that nuclear terrorism is now one of the greatest threats to international security.

How we work together to counter this threat by limiting the amount of nuclear material in circulation and strengthening controls is the focus of the summit this week. This is also an area where Kazakhstan has unique and relevant experience.

One of the legacies of the tests at Semipalatinsk was a large volume sensitive information, infrastructure and radioactive material left unsecured around the vast complex. The very real danger was that this knowledge, equipment and materials could fall into the wrong hands and be used to make an atomic bomb.

Over 10 years, experts from Kazakhstan, Russia and the United States carried out an unprecedented joint program to find and secure the remnants of the Soviet nuclear program. National interests in this most sensitive of areas were put aside for the higher goal of international peace and security.

No matter what the immediate difficulties, we need to find the same vision and level of international co-operation at The Hague. I hope that through our discussions, we can identify a range of practical measures to improve nuclear security and, most importantly, demonstrate the political will to put them into action.

At the heart of this challenge is how we can successfully balance the wholly legitimate right of countries to pursue civilian nuclear energy while tightly regulating the production and use of highly enriched uranium to minimize the risk of further proliferation by state or non-state actors. Kazakhstan strongly shares the view of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA ) that the solution is to provide countries with a guaranteed supply of fuel to power nuclear plants. This is the aim of IAEA plans for an international low-enriched uranium bank, which we have offered to host on our territory.

As the world’s largest producer of uranium and a proven expertise in providing security at nuclear facilities, Kazakhstan has excellent credentials for the role. Importantly, we also have good relations with all existing nuclear powers and those countries seeking to develop a civilian nuclear-power sector.

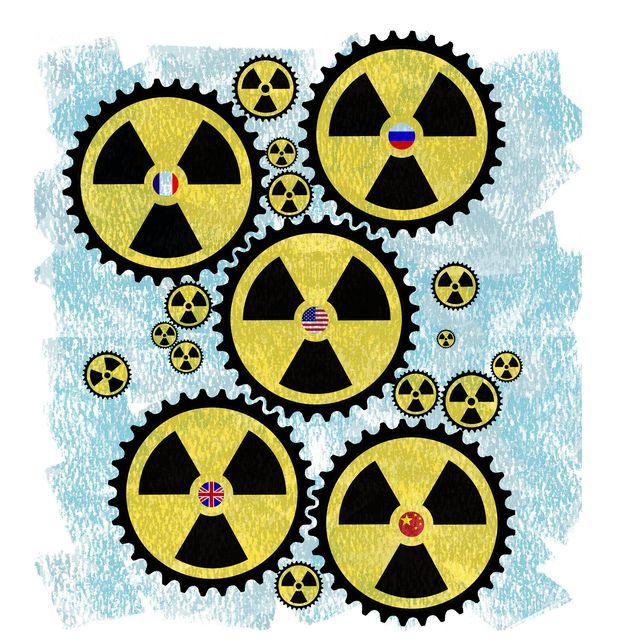

However, to increase confidence, Kazakhstan also strongly believes that the present Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty needs to be modernized and better balanced. At the moment, for historic reasons, the non-proliferation regime hands the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France and China considerable technological and economic advantages.

It is frankly unfair that the original five nuclear-weapon states are free from the obligations which require all other signatories to provide the IAEA complete information on their civilian nuclear programs, projects and plans — information with significant potential commercial value. We need to find a way which, while taking into account the sensitivity of the information, ensures every country reports to the world community that they have met their non-proliferation obligations.

This could be achieved under the U.N. Security Council mandate by setting up a special committee to which the nuclear-weapon five states would report. The sessions could be restricted to preserve confidentiality, but the final document setting out its findings would be accessible to all member states. Such a change would help retain and build confidence in the present system of nuclear non-proliferation.

В Атырау -10

В Атырау -10